https://tonic.vice.com/en_us/article/3kyza5/opioid-overdose-suicide

Maria Luisa Tucker

Maria Luisa Tucker

“Pick up or drop off?” the pharmacist asked.

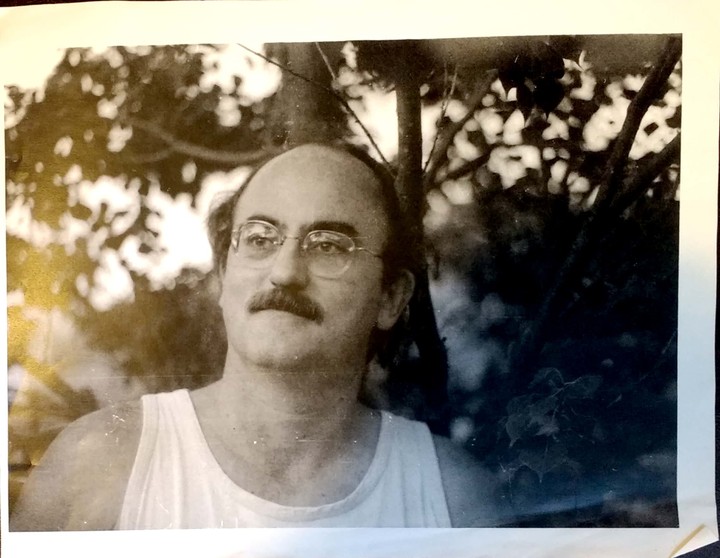

“Actually, I’m distributing these,” I said, holding out a flier that read “Dad, Where are you?” above a photo of my 52-year-old father. His brown eyes were dull behind thick glasses, his mouth locked in a slight frown, his thin hair combed neatly back from a receding hairline.

I could tell the pharmacist recognized the photo by the way his eyebrows shot up.

“I’m his daughter,” I said. I knew there were laws against giving anyone information about a patient, so I just stood there and let the silence unfold. Finally, the pharmacist began tapping at his keyboard.

“He refilled some prescriptions,” I continued, as he looked again at the flier, “a few days before he went missing.” He made a little hmph sound and looked at me sadly.

“If I see him, I’ll call you,” he offered.

I thanked him and wandered into the nearest aisle, where I gazed at the boxes of Band-Aids and made mental calculations: If he’d been here a few days before he disappeared into the 3-million-acre national forest that abutted his house, that meant he had a full bottle of hydrocodone, the generic version of Vicodin. A full bottle could last him a couple months, if he rationed them. But a full bottle could also shut his lungs down if he decided to take them all at once.

Long before the opioid epidemic made headlines, I knew my dad had a pill problem. A mechanic, he carried a green monogrammed satchel—we referred to it as “Dad’s purse”— that contained a dozen medications, including the daily painkillers he used to soothe back pain from years of leaning over cars. He had never been happy exactly, but the drugs seemed to dampen the few joys he had. By the time I was in college, he had stopped baking experimental batches of bread for fun and had lost his affinity for bad puns. When I moved 2,000 miles away for grad school, he stopped returning my phone calls because, he said, “he didn’t have anything good to report.” When I visited for Christmas the year before he killed himself, he was moving slow and my stepmom complained that he was addicted to his pills. Then he disappeared into the forest.

That was in 2006, when painkiller prescriptions were still on the rise. For years, I thought of my dad’s suicide as just a personal tragedy. I realized it was a trauma repeating itself around the nation only after I saw a New England Journal of Medicine article estimating that “somewhere between 20 to 30 percent” of opioid overdose deaths may actually be suicides. “It could be even higher,” the authors wrote ominously.

More from Tonic:

The shocking numbers are more educated guess than documented fact, since thousands of overdose deaths are classified as “undetermined” rather than intentional or accidental. “Absent a suicide note, we don’t have a consistent nor reliable way of calculating how many of the estimated 42,000 opioid-overdose deaths in 2016 were the result of suicide attempts,” says Nora Volkow, co-author of the NEJM article and director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. But she and co-author Maria A. Oquendo, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, present a compelling case that suicide is a silent contributor to the opioid epidemic death toll. Among the most telling evidence they offer is from emergency rooms. About half of the opioid overdoses treated in ERs were deemed accidental—and 26 percent were for intentional overdose. Another 20 percent were “undetermined.”

My dad might have been counted among those ER numbers as an “undetermined.” Several months before his death, he had gotten dehydrated, taken too many painkillers, and collapsed in the street. The doctor who treated him told me in an exasperated tone that my father was “close to renal failure and needs to take better care of himself.” I tried to talk to my dad about his pill addiction and back pain, suggesting that he do yoga or go to therapy. He laughed in a way that said I was naive and, at 26, I probably was. He was already too far down the black hole of physical pain, dependence, and hopelessness that many opioid users find themselves in.

Like some of the 2 million people who abuse pills or heroin today, my dad’s relationship with opioids had started out with one doctor’s appointment. Back pain led to surgery, which led to painkillers. In the early aughts, doctors were still being encouraged to prescribe the “miracle drug” OxyContin and other slow-release opioids. But the surgery didn’t work (as many back surgeries don’t) and the pills didn’t fully eradicate the knifelike pain.

Chronic pain and mental health work in a feedback loop. “Pain increases suicide risk, so treating pain is likely to reduce suicide risk,” says Amy Bohnert, a health services researcher at the University of Michigan Medical School and the Ann Arbor VA. The problem is that the main pharmacological treatment for pain, opioids, can bring a patient’s mood down. In a study of Veterans Affairs patients on “higher doses of opioids had a greater risk of suicide than patients on lower doses,” Bohnert tells me.

In fact, patients who were not depressed when they began using opioids had a 35 to 105 percent increased risk of developing depression if they remained on opioids for 90 days or more, compared to those who stopped opioid use within 30 days, according to a 2016 study from the St. Louis University School of Medicine. Opioids can cause long-term changes in the brain’s reward centers, so “depression might be a reaction to not being able to feel pleasure in things that used to bring pleasure,” explains Jeffrey Scherrer, the lead researcher of that study.

When he told me that, a distinct memory flashed, of me sitting on the porch of my father’s Arizona home shortly after he moved there, wondering why he seemed to be blind to the beauty of the Ponderosa pines that towered above like skinny skyscrapers. His new home was in the kind of cool mountain town he’d daydreamed about when we’d lived in the hot, flat center of Texas.

A month after my dad disappeared into that Arizona pine forest carrying just his satchel, a detective called to say he found his body in a drainage pipe under the dirt road that led to his house. My dad had wriggled in, used his satchel as a pillow, turned on a flashlight, and opened up a sci-fi novel. Then he’d taken all his pills and read himself to death.

As the death toll continues to rise—there have been more than 350,000 opioid-related deaths since 1999—suicide prevention organizations have begun to recognize opioids as an urgent issue. It’s important to try to distinguish whether an overdose was accidental or intentional because the path to treatment may be somewhat different, says Jill Harkavy-Friedman, the vice president of research at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

More access to effective treatment is the obvious key to turning the tide on the overdose epidemic. All treatment programs should offer medications to treat opioid addiction (buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone) and should have board-certified addiction specialists and mental health workers on staff, says Kelly J. Clark, president of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. Unfortunately, Clark says, the majority of treatment programs don’t offer those things and patients who relapse after treatment are even more vulnerable to suicide. And for suicidal people or those who have survived an intentional overdose, Harkavy-Friedman says that treatment must also “tackle the suicidal ideation and behavior directly so the patient can develop a way to cope with those things when they emerge.”

A month before our dad went missing, my brother and I had half-heartedly joked that we should tie our father up and drag him to treatment. It’s hard not to feel a twinge of regret that we didn’t actually try a dramatic intervention now, as I read about an outpatient clinic at Stanford that has helped some patients successfully taper, very slowly, off the opioids they were addicted to. Or when a researcher writes to me to tell me that “patients with depression who received adequate antidepressant treatment were more likely to stop using prescription opioids—even patients who had been on them for years.”

The key difference between those patients and my dad, however, was that my dad never even considered treatment. “You can’t always make somebody do what you want,” Harkavy-Friedman says. “But you can start by having a conversation telling people what you’re concerned about. Oftentimes, they’ll say, ‘no, I’m fine’ so you have to be persistent. And you can also contact the person’s doctor. They may not feel that they can talk to you because of confidentiality, but there’s nothing that bars you from talking to them .”

I didn’t want to talk about the possibility of overdose or suicide in 2006, but now know that we can’t afford to avoid those uncomfortable conversations. Opioid users, their families, their doctors all need to figure out how to address the dark realities that could await.

Comment;

This sad piece reinforces the need to treat dual-diagnosis; comorbid mental health disease/disorder with addiction. Buprenorphine/Suboxone is very helpful.

- COVID UPDATE: What is the truth? - 2022-11-08

- Pathologist Speaks Out About COVID Jab Effects - 2022-07-04

- A Massive Spike in Disability is Most Likely Due to a Wave of Vaccine Injuries - 2022-06-30