https://whyy.org/articles/dont-call-people-addicts-penn-researchers-say/

Addiction researchers at the University of Pennsylvania say it’s time to stop using “addict” and “alcoholic” when talking about people with substance use disorders. The recommendation comes out of a new study that found the terms are associated with a strong negative bias.

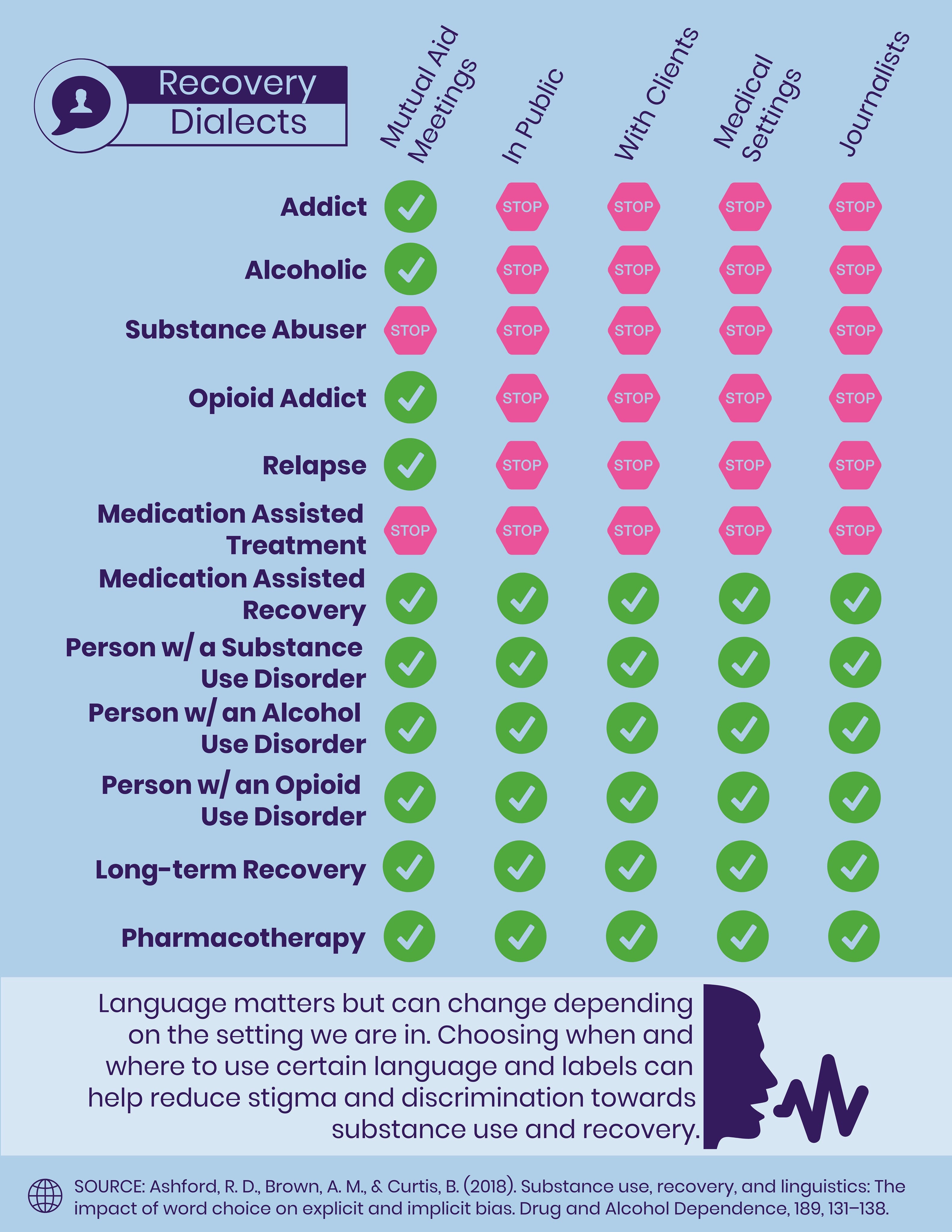

Researchers studied how people responded to several addiction-related terms including “addict,” “alcoholic,” and “substance abuser.” Those terms elicited the strongest negative biases of the lot, said lead study author Robert D. Ashford.

“Terms that seem to label the person — and invoke the negative attitudes toward the person rather than the disease — those are the ones that have the higher levels of bias,” said Ashford, a research assistant at the University of Pennsylvania and doctoral candidate in health policy at the University of the Sciences.

Participants were asked questions about their willingness to associate with people depicted in fictional vignettes who were described with such terms. But the study also used a word-association task to test whether any “implicit bias” was lurking in the language.

“So ‘implicit’ is … think of ‘subconscious,’ what’s going on in the recesses of my mind that I may not be consciously aware of,” Ashford explained.

The study was the first to examine implicit biases in labels for people with addiction, he said. The method researchers used to measure it derives from the “implicit association test” used to identify unconscious racial biases.

Researchers also looked at alternatives to these terms that are seen by advocates to be less stigmatizing, such as saying “person with a substance use disorder,” instead of “addict.” Ashford said this “person-first” language was associated with less negative implicit bias in their study.

Ashford said the study built upon previous research that found terms such as “substance abuser” could make mental health clinicians less inclined to work with hypothetical patients described that way.

But when it came to more conscious biases against people with substance use disorder — known to researchers as “explicit bias” — all of the terms investigated in the study elicited similarly strong negative reactions. This result was based on the “social distance” participants preferred to keep from people described in the vignettes (for example, whether they would want them as a neighbor or a co-worker).

Ashford said this could be partly explained by the fact that many people have had negative experiences with addiction itself.

“We’re not talking about unicorns and rainbows, we’re talking about a very serious part of the human condition that has a lot of feelings and emotions attached to it — and many of them bad,” he said.

Still, he said, avoiding terms such as “addict” and “alcoholic” and adopting person-first language could help reduce negative biases over time. Wider adoption of this kind of language, particularly by public officials and the media could help reduce the stigma that stops some people from seeking help, he said.

Last year, the Associated Press recommended that news organizations use person-first language and avoid terms such as “addict.” In April, the Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News adopted a similar policy.

Comment;Words ARE important, there is already enough stigma with this disease. We DO need to face what is really going on, but sometimes it can be done with an iron fist, other times require a velvet glove.

- COVID UPDATE: What is the truth? - 2022-11-08

- Pathologist Speaks Out About COVID Jab Effects - 2022-07-04

- A Massive Spike in Disability is Most Likely Due to a Wave of Vaccine Injuries - 2022-06-30